Troughs

Troughs

Installation: Red Head Gallery, 401 Richmond, Toronto, 2005

-

Six cement troughs filled with water

-

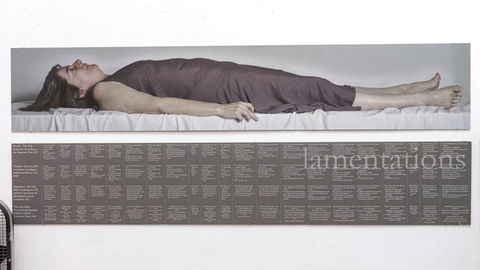

A photographic self-portrait, after Holbein’s "Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb" Photo by Brian Piitz and Marilyn Nazar

-

A text panel with excerpts from four translations of the Book of Lamentations, in which the destroyed city of Jerusalem is a metaphorical widow

IMAGES

ABOUT TROUGHS

Catalogue essay by Daniel Baird:

In Hans Holbein the Younger’s great panel of 1522, “The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb,” which most likely formed part of an altarpiece, the dead Christ is depicted full length, stretched out on a roughly sheeted plinth. His hair and beard are scraggly, his mouth is agape, his empty, stricken eyes gaze upward. Christ’s body, which is treated with such tenderness and sensuality in the work of Italian masters like Raphael, is emaciated and wounded, his skin tinted a pallid, sickly green. “The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb” is not a painting of ensouled flesh elevated by suffering, a transcendent Man of Sorrows, but is rather a grotesque portrait of a hastily entombed corpse in the aftermath of humiliation and torment -- not even the dark, coagulated blood has been washed from his feet. Holbein painted a dead Christ in which it is virtually impossible for us, finite mortals, to imagine his suffering being transcendent or his body resurrected.

For one of the central images in her exhibition Troughs, Robin Pacific had herself photographed in a posture that closely mimics that of Christ in “The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb.” Dressed in a simple, dark, sleeveless dress, she is stretched out on a sheeted slab, her mouth open and her eyes gazing upward; like Holbein’s Christ, Pacific’s hand clasps the edge of the stone on which she rests, as though literally clinging to the tomb. The print, which has roughly the same long, horizontal dimensions as the Holbein painting, has been given a cool, damp, grey-green sheen, suggesting both sickness and the earthy depredations of the grave. But whereas Christ’s body is deformed by torment, Pacific’s body is heavy and passive; whatever suffering she has endured is invisible and inward. While Christ’s body in the Holbein painting looks vacant and irredeemable, Pacific’s body is distinctively alive: she looks as though she is waiting for death, as though she is attempting, by negating the world, to separate her soul from her body and transport it to the other world. Yet the wall dividing the living and the dead is absolute, the tomb’s thick stone serving as both a physical and a metaphysical divide; death itself cannot be experienced from the point of view of the living. Pacific’s self-portrait has all the dark circularity of bottomless mourning.

Parallel with her reenactment of “The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb,” and printed on photographic paper in the same horizontal format, are a series of translations from the prophet Jeremiah’s Lamentations. “How doth the city sit solitary, that was full of people,” Jeremiah begins in the influential King James version, “how is she become as a widow! She that was great among the nations…” And then, “She weepeth sore in the night, and her tears are on her cheeks: among all her lovers she has none to comfort her.” If the achingly erotic Song of Solomon (“I sat down under his shadow with great delight, and his fruit was sweet to my taste”) is the great Biblical poem of love and desire, then Lamentations is an emotionally wrenching poem of abandonment, bereavement, and exile: “For these things I weep, mine eye, mine eye runneth down with water, because the comforter that should relieve my soul is far from me.” The narrator in Lamentations has been eviscerated, emotionally and spiritually; he has become a stranger to himself by having been repudiated by God. Robin Pacific’s self-portrait is an image of widowhood and exile from one’s deeper soul. She is trying – and failing – to submit to the seduction of oblivion.

The two wall pieces in Troughs are both about despair over, and mourning for, the loss of a loved one, and it is what we love that gives coherence and meaning to our worlds, both inner and outer. When mourning turns to what the French symbolist poet Gerard de Nerval called the “Black Sun of Melancholia,” it is accompanied by a radical emptying out of the meaning of words and images. Yet at the same time, in the religious traditions Troughs persistently alludes to, both Christian and Jewish (it is significant that Pacific provides multiple translations of passages from Lamentations), exile and death, bereavement and sorrow, are virtually preconditions for ultimate transcendence. The grotesque, entombed Christ in Holbein’s painting must be viewed as part of a story that ends in resurrection and glory; in an intact altar, Christ rising in a burst of light would have been above the image of him defeated in the tomb. And it is crucial to understanding the abject, volatile tone of Lamentations, its visionary self-loathing, to recall that it also contains passages like this: “It is of the Lord’s mercies that we are not consumed, because his compassions fail not. They are new every morning…”

On the floor beneath the two wall pieces sit six narrow cement troughs, filled with water. The surface of the cement has been patinaed to the greyish green of Christ’s skin in the Holbein painting, a color which is at once morbid, melancholy, and strangely sensuous. I mention these austere, heavy troughs last, despite their being the works, which give the show its title, because there is a sense in which they follow from the more discursive pieces on the wall. Lit from above in direct, subdued light, the troughs are sepulchres, but they are open, and they are filled, not with defiled corpses or forgotten bones, but with an image of the spirit: water that is clear, still, and serene. In her self-portrait as dead and in the tomb, Pacific seems remote, closed off, and opaque; the troughs, by contrast, are not so much grim as humble and open. In the great Kabalistic theosophy of Isaac Luria, the cosmic “breaking of the vessels” casts the souls of the chosen into exile, only to be gathered back together in the time of redemption. Troughs, however, is neither mystical nor messianic. The troughs are covered with dark flaws, but they still hold water. The water reflects. One can dip one's hands into it, and drink.

The course of human life – of mortal life, of life in time – is largely defined by a struggle with loss: of the people one loves, of belief, of faith, of meaning. Mourning, and the melancholy that accompanies it, is perhaps the natural state of consciousness. Even if loss and suffering can be spiritually transformative forces, the wounds and the damage inevitably remain. In his pivotal essay “Mourning and Melancholia,” Freud claims that the threat of mourning turning into a destructive, pathological form of melancholia is in part that of ceasing to be able to acknowledge the presence and significance of the external world, of remaining within the closed tomb of the mind. Pacific’s troughs quietly imply the possibility of openness and clarity, of love and perhaps even wisdom, from serenity founded upon our damaged condition.

Email from artist Lynn Campbell:

I wanted to congratulate you on your exhibition. I was quite moved by the installation, and most particularly by the photograph of you. As well as being a beautiful image, and seemingly serene at first, it was also powerful in the depth of feelings portrayed. Although I did not know your husband, your sense of loss and mourning was immediately apparent and felt. The death of someone close reminds us of what is important and may give us back our soul, but still the cruelties of life seem senseless. They tarnish our optimism and challenge our faith, and yet, oddly, they retain the power to make us ever more human.